Shameless.

That secret that you know

That you don't know how to tell

It fucks with your honor

And it teases your head— Bon Iver, Blood Bank

The Secret

Bon Iver is an American indie folk band founded in 2006 by singer-songwriter Justin Vernon. Blood Bank is their 2009 EP, the title track being a leftover from their previous 2008 album (For Emma, Forever Ago) that didn’t fit with that set of recordings.

Vernon told NPR that the Blood Bank track was a fictional love story, a rumination on the magic of an undefinable bond. "I think that that secret in the chorus is the answer to all those questions," he suggested. "Why is this sacred and why does this feel larger than myself and larger than what I can even put into words ... I think it's the connection that we have to each other."

The secret we don’t know how to tell? The desire to be connected to someone. It makes us feel vulnerable, and we’re afraid to go there.

Daring Greatly

On April 23, 1910, a year after he left office, Theodore Roosevelt gave a speech at the Sorbonne called “Citizenship in a Republic” (the speech is also known as “The Man in the Arena”). Roosevelt commended those who dedicated themselves to bettering the world and condemned the cynics who criticized their efforts without doing anything themselves to advance the common good.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Brené Brown has written a whole book on Roosevelt’s phrase, daring greatly. Her 2021 bestseller, Daring Greatly, focuses on risking vulnerability, especially in our relationships. Brown says, “We must walk into the arena, whatever it may be—a new relationship, an important meeting, our creative process, or a difficult family conversation—with courage and the willingness to engage.” We cannot sit on the sidelines. We cannot merely observe and critique. “We must dare to show up and let ourselves be seen. This is vulnerability. This is daring greatly.”

This blog is about looking at relationships through a spiritual warrior lens and recognizing that love is a spiritual battle that begins within. We all have good and bad, dark and light, inside of us. We need to come to terms with this ambiguity … even/especially in our relationships with others. Our tendency is to deny the bad, with the faint hope of convincing others (if not ourselves) that we somehow have it all together. If we can’t maintain that façade, we swing over to the other side of the pendulum and write ourselves off as a complete failure—we’re hopeless, we’ll never get better, so why even try? Ultimately, both of these extreme responses distract us from dealing with our shit.

Being vulnerable means facing our shame. Shame feels awful. It washes over us, consumes us, and shuts us down. So, we avoid it. But we need to welcome these unwelcome feelings so we can face them down, get through them, and keep fighting for love.

Toxic Shame

The puritanical elements of Western culture have promoted the belief that shame is good for keeping people in line. There’s no research that correlates shame with good behaviour. Shame is dangerous. “Toxic shame,” a term first coined by affect/script theory psychologist Silvan Tomkins and popularized by author John Bradshaw (Healing The Shame That Binds You), comes from internalized messages of being unworthy of love and belonging. This creates feelings of hopelessness or helplessness, which can develop into anxiety and/or depression. Substance abuse and addiction are also common: the buzz or high of alcohol or drugs replaces the warm, fuzzy feelings associated with oxytocin, the social bonding hormone that is depleted when shame isolates us from others.

Shame makes us feel we’ll never find the connection we want with someone else.

… it’s the fear that something we’ve done or failed to do, an ideal that we’ve not lived up to, or a goal that we’ve not accomplished makes us unworthy of connection. I’m not worthy or good enough for love, belonging, or connection. I’m unlovable. I don’t belong.

— Brené Brown

Shame makes it difficult for us to enter meaningful relationships. Or, if we risk relationships, we find it hard to stay in them. Even relatively minor challenges in relationships can generate a tsunami of reactive emotions within us. We lash out at people, we hide from people, or we simply shut down and tune out the people around us. Most of the time, the people in our lives have no idea what’s going on.

What’s going on is a stress response. Shame is when the prefrontal cortex, where we do all of our thinking, analyzing, and strategizing, gets overrun by the limbic system, which is the primitive fight/flight/freeze part of our brain. We come out swinging, or we run, or we just feel completely powerless and go numb. Brené Brown shares some of the ways her readers describe their shame responses:

“When I feel shame, I’m like a crazy person. I do stuff and say stuff I would normally never do or say.”

“Sometimes I just wish I could make other people feel as bad as I do. I just want to lash out and scream at everyone.”

“I get desperate when I feel shame. Like I have nowhere to turn—no one to talk to.”

“When I feel ashamed, I check out mentally and emotionally. Even with my family.”

“Shame makes you feel estranged from the world. I hide.”

“One time I stopped to get gas, and my credit card was declined. The guy gave me a really hard time. As I pulled out of the station, my three-year-old son started crying. I just started screaming, ‘Shut up…shut up…shut up!’ I was so ashamed about my card. I went nuts. Then I was ashamed that I yelled at my son.”

Why is the shame response triggered so easily in some of us? Trauma is a major factor. People who have been violated and attacked internalize messages of being unworthy and unlovable: “I’m broken,” “I can’t love anyone,” “No one will ever love me, respect me, care for me, protect me,” etc. When a negative experience in a current relationship occurs, it reactivates our internalized messages of defectiveness and triggers an emotional reaction disproportionate to what we’re actually facing in the moment.

Our family of origin is also a major contributor to shame. As soon as life begins, our brains start forming impressions of how our needs are met by our caregivers. Our interactions with them are stored in our limbic system, which is where our implicit memories are held. (Implicit memory is sometimes referred to as unconscious memory or automatic memory—it draws on past memories to generate responses without our thinking about them.) If we ran onto a busy street or wet the bed, we likely received one of two responses: 1) someone told us what we did was wrong but reassured us that everything was okay, or 2) someone lashed out at us—“Why do you always do this? What’s wrong with you?”—and provided no reassurance. Our implicit memory internalized those responses and keeps generating messages that drive how we process difficult and challenging circumstances in the present tense. We either respond with the ability to recognize our mistakes and assure ourselves we can do better, or our inherent sense of being defective and inadequate is triggered, and we go into fight/flight/freeze mode.

Shame is a catch-22. We want to stop the reactive fight/flight/freeze cycle in our lives, but that requires self-reflection—taking a look within. But we don’t want to take a look within because we’ve bought into the lie that we’re defective and inadequate, and we fear that self-reflection will only confirm our worst suspicions about ourselves. So, we keep turning to fight/flight/freeze mode every time a problem or challenge occurs in a relationship … and the cycle continues.

There is no magic pill to make shame go away. Cognitive behavioural therapy, which is typically effective with anxiety and depression, is not typically effective with shame because shame is an autonomic response, not a cognitive one. Gerald Fishkin, a psychotherapist and author of The Science of Shame and Its Treatment, uses compassion-focused therapy, which encourages people to see themselves (and others) through a more compassionate lens. This is similar to Gabor Maté, who encourages people to develop the practice of compassionate self-inquiry:

Taking off the starched uniform of the interrogator, who is determined to try, convict, and punish, we adopt toward ourselves the attitude of the empathic friend, who simply wants to know what’s going on with us. The acronym COAL has been proposed for this attitude of compassionate curiosity: curiosity, openness, acceptance and love: “Hmm. I wonder what drove me to do this again?”

If we don’t begin with compassionate curiosity toward ourselves, we become defensive. We dig in instead of letting go and becoming the person we can become. If we show compassion to ourselves, we can drop the shame and focus on who we are capable of becoming.

Shame Resilience

If we want to be fully connected to someone, we have to be vulnerable—we have to risk revealing who we truly are to another person. The word vulnerable comes from the Latin word vulnerare (“to wound’”). So, being vulnerable literally means being wound-able. It’s the quintessential definition of what it means to be “lovers in a dangerous time” (Bruce Cockburn) and where love is always “some kind of fight.”

Being vulnerable will always feel risky, even reckless at times. But the adage, “no risk, no reward,” applies to relationships more than anything else in life. Love is not safe. There are no guarantees. We have to enter our relationships as spiritual warriors, not with our defences up, but with a recognition that we may get wounded and, more importantly, the realization that we can recover from our wounds. We need to develop shame resilience.

Brené Brown describes shame resilience in terms of recognizing our pain but drawing from our courage too:

Shame resilience is the ability to say, “This hurts. This is disappointing, maybe even devastating. But success and recognition and approval are not the values that drive me. My value is courage and I was just courageous. You can move on, shame.”

Resilience typically involves cognition or thinking, but shame bypasses the thinking part of our brain (the prefrontal cortex) and is powered by the limbic system (the reptile brain). Therefore, something more primal than a cognitive approach is required to develop shame resilience.

Brené Brown describes her primal response as murmuring to herself, over and over again, “Pain, pain, pain, pain, pain.” This pain chant works for her because it lets the lizard brain run itself out and pulls the prefrontal cortex back online. After one or two minutes of pain chanting, she takes a deep breath and says to herself, “I’m okay. What’s next? I can do this.” Brown also uses something akin to Gerald Fishkin’s compassion-focused therapy to take the next step, extending to herself the same understanding she would extend to someone else in her situation:

Talk to myself the way I would talk to someone I really love and whom I’m trying to comfort in the midst of a meltdown: You’re okay. You’re human—we all make mistakes. I’ve got your back. Normally during a shame attack we talk to ourselves in ways we would NEVER talk to people we love and respect.

Brown also “owns the story,” rather than buries it: “If you own this story you get to write the ending.” She references Carl Jung’s infamous aphorism, “I am not what has happened to me. I am what I choose to become.” We screwed up. We lost in love. It didn’t work out. Now, we get to decide how to move forward. We’ve survived and perhaps even emerged stronger, and we can continue the fight for love.

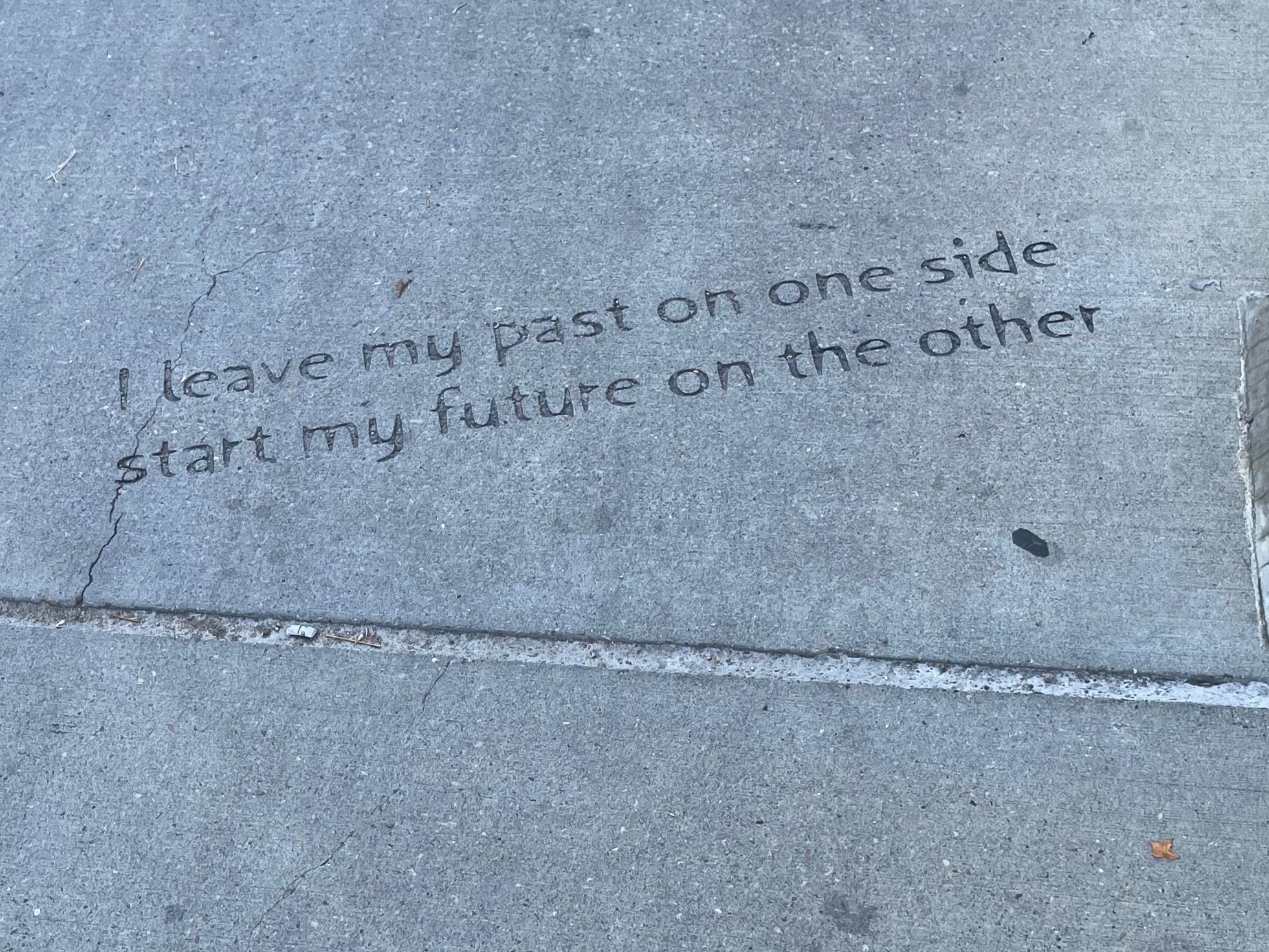

High Level Bridge (109 St., Edmonton, AB)

Love Shamelessly

There are no easy relationships. Loving someone will always mean daring greatly. It will always mean having the courage to let our vulnerable selves be seen and known. It will mean getting wounded occasionally, maybe often. We can play it safe and never get wounded, but we can’t experience love that way.

Being spiritual warriors means not letting shame knock us out of the fight. Feel the pain; don’t feel the shame. Don’t let your reptile brain tell you you’re unworthy and unlovable. Remember who you are. Admit your mistakes and learn from them. Claim your inherent value as a human being. Keep going.

Shameless is a bad word in our society, but shameless love is what we all need and want. Love shamelessly. Someone out there is trying to love shamelessly, too, and waiting for someone like you.

You see there's always

some way back

Don't close the doors

to hide your heart

You know it can't keep beating

in the darkLift up your head,

break down the walls

Don't stop pushing

'til they fall

At first the sun might

hurt your eyes

But soon you'll see

the beauty in the light— Hollow Coves, Beauty in the Light

(With thanks to Natalie Maksym and the return of her amazing figure skating vids for putting this record on my radar.)